MISE

Instalace sousoší v Parku J.A. Komenského ve Zlíně

Květen 2021 - duben 2022

Autor Fotografií: Libor Stavajník. Foto TOAST

LEOŠ LANG kurátor:

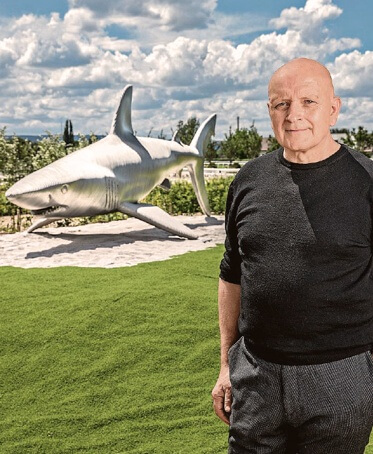

Po realizovaných výstavách v roce 2019-2020 na zlínském zámku v Galerii Václava Chada, Michal Gabriel „V BARVĚ A STRUKTUŘE“ kde se autor představil ve čtyřech výstavních prostorách průřezem své tvorby převážně polyesterových soch a na nádvoří zámku a v prostoru před zámkem ocelovými objekty-Šelma a Žralok realizovaných ve spolupráci s fy Kasper a v galerii GꝎZ Oční optik Mezírka „OPTIKOU SOCHAŘE“ s kombinací polyesterových a drobnějších bronzových plastik a objektů z lité nerezové oceli jsem dostal od autora nabídku na projekt „Sochy v prostoru“. Po několika konzultacích byl vybrán zlínský park J.A. Komenského. Po oslovení zlínské radnice-radního pro kulturu ve spolupráci s odborem kultury a památkové péče také architektem revitalizace parku a schválení Radou města Zlína byl realizován projekt 20 bronzových soch v městském parku.

Je to další realizace kdy řadu svých soch Michal Gabriel zasazuje do nejrůznějších prostorových kontextů a zkoumá, jak může socha ovlivňovat prostředí a naopak.

Je zde přítomná a dobře patrná tvůrčí vytrvalost, s níž se autor přibližuje k danému nebo zvolenému tématu, a to téměř až k významově baroknímu spojení a vyjádření vztahu: socha a příroda.

MICHAL GABRIEL sochař, autor:

Do Zlína jsem nainstaloval a pro tuto příležitost nazval sousoší Mise. Sousoší je sestaveno ze dvou původních sousoší, které jsem nazval „Smečka“ a „Hráči“.

Smečka – sedm kočkovitých šelem prochází prostorem jedním společným směrem. Sousoší vznikalo postupně procesuálně od poloviny devadesátých let a svoji konečnou podobu v bronzu dostalo v roce 2007 Sochy jsou modelované do hlíny a potom odlité do polyesterové pryskyřice a struktury tvořené ze skořápek vlašských ořechů, a nakonec odlité do bronzu.

Hráči – třináct Mužských postav s protaženýma rukama. Sochy začaly postupně vznikat od roku 2000.

Každá socha je původně vysekaná do dubového kmene a na každé jsem pracoval necelý rok. Sousoší jsem ukončil počtem třinácti soch v roce 2010. Postavy jsou zachycené v nakročených posicích a jejich protažené ruce jim zajišťují pocitovou i fyzickou stabilitu. Ruce se proměňují v nástroje, hrací pálky, zbraně. Postavy instalované jako sousoší Hráči jsou obráceni dohry a z prostoru který vymezují a ohraničují vytvářejí svůj prostor hry. Po transformaci postav hráčů do stejné struktury, jakou má sousoší smečka bylo možné obě sousoší propojit a vytvořit z nich nové sousoší ve které jdou všechny mužské i zvířecí postavy jedním směrem.

Mise – sousoší instalované ve Zlíně. Sousoší bylo před tím vystaveno v Karlových Varech pod názvem Hráči. Pro Zlín dostalo nový název. Postavy a zvířata procházejí přítomným prostředím jako by se vynořily z archetypálního světa podvědomí. Světa, se kterým jsme všichni vědomě i nevědomě propojení, ze světa s nereprodukčním smyslem života.

Charles IV monument installation – Divadelní náměstí Karlovy Vary (May 2022)

Height of the monument: 6 metres

Weight: 20 tonnes

Material: stainless steel

Author: prof. Stainless steel: 20 years old, 20 years old, 20 years old, 20 years old, 20 years old, 20 years old,

Co-author. Arch. Michael Gabriel,

Made in: Kasper

Investor: Rotary klub Karlovy Vary

The monument was created as a design for a competition announced in 2017 by the Rotary Club of Karlovy Vary. The conditions of the competition stipulated not only the design of the monument but also the selection of a place for its future location. Therefore, I decided to work with the monument as if it were a free sculpture. The monument was not purposely based on the surrounding area of its future location, as no location was specified in the brief. During the final work on the model, my co-author and I selected several possible locations, and among them was Theatre Square.

The idea of the monument is based on the combination of traditional form with new contemporary technology and new material. The outline of a rider on a horse perched on a rectangular block of plinth represents a clear and established form of a monument as it was often built-in history. Tradition and the past are embedded in the sculpture's shapes and emphasize permanence. I consider the ability to endure over time to be one of the traditional requirements for a statue. The present is inscribed in the monument by the technology and material used. This is not even the millennia-tested bronze or granite but stainless steel.

The basic sculptural concept of the monument is to conceive of the whole monument as a statue of a great reliquary or as a statue of a monument. That is why the monument has two plinths. The first plinth is firmly connected to the sculpture as a whole. The pedestal is as important as the statue on it, as it becomes a semi-transparent shell of St Wenceslas' crown embedded in it from the side view. The second plinth is made of concrete and is part of the future architectural design of the square.

The statue - that is, the equestrian statue together with the plinth - is assembled from layers of 10 mm thick stainless steel plates. The sheets are laser cut. The cut surfaces reflect light and cover more than half of the surface of the statue. The colour of the whole sculpture thus changes with the colour of the surroundings during the day and night. The sculpture takes on a special lightness and in some lighting conditions can resemble a materialized hologram. The inspiration for this way of working with steel sheets came from 3D printing technology. Unlike printing, the layers are wanted and deliberately 10 mm thick. Their rotation and inclination towards the shapes of the monument are one of the expressive means of the surface structure. It predetermines the light reflections and allows for the lateral transparency of the plinth. The structure looks light and of course but technically it is quite complicated. I dare say that not many sculptors work in this way. As far as I know, no one has used the effect of inserting a crown into a plinth. In the technical solution of the sculpture lies also a substantial part of the work of the co-author.

The process is inspired by 3D printing, which also works with layers placed precisely on top of each other. Unlike 3D printing, the individual layers do not try to merge but instead become a distinctive structure that supports the expression and feel of the entire steel sculpture. The layers rhythms the surface of the sculpture by the way they cut through it. The individual layers are made of centimetre-thick stainless steel plates cut into contour shapes by laser. The cut edge of each plate thus forms a substantial part of the surface of the entire sculpture. The optical properties of stainless steel, its ability to not corrode and thus permanently reflect light, gives the surface of the sculpture completely new properties. The sculpture is constantly changing colour as the light changes during the day. Finally, the material used also gives the sculpture the basic requirement that has accompanied sculptures since the first birth of art, which is the emphasis on the ability to endure over time. To carry its message over time over millennia. In Egypt, such material was granite, in ancient Greece, bronze, and these materials are still available to us today. Now they are joined by stainless steel. These materials also required appropriately advanced technologies to process or cast them. These technologies are an expression and imprint of the time in which the works of art were created and further refined and developed by later artists and craftsmen. Works created in these traditional technologies in their peak forms achieve perfection and originality. But they never again achieve material surprise. Only with the discovery and use of new material and new technology can this moment come into play. It is always linked to the time that first made it possible. This is precisely why he would not be able to give this material precisely controlled shapes and thus not completely subordinate it to his intention.

That is the magic of the sculptures thus created. This allows the subject to be very simple and many times elaborated. A new perspective on these themes gives a new form appropriate to the present time.

What led you to start using modern technology in your works?

I have always considered technology to be an important creative tool, one which makes a fundamental imprint on the ultimate effect of a work. I have always kept up with and used new materials and new work methods in the creation of my statues. I don’t do it ostentatiously, so the viewer may not even realise it; nevertheless, I think that the traces of this approach contain and acquire a frequently unmistakeable form. At the moment when digital technologies appeared in art, with the possibility of real, material forms of works using 3D printing or 3D cutting, I started using them. I sensed in them a gateway to a new creative space that opened both new themes and new forms of statue.

When did you first encounter art – did someone introduce you to it?

I think I found my own way to the visual arts, even though we were into art at home. My mum was interested in theatre and my grandpa was a pianist – an amateur pianist, but they say he was very good. We had quite an extensive library, which included books about the visual arts. My parents took me to exhibitions, so I accepted art as an essential part of my life.

Do think that there is a deeper meaning in your works – do they leave a legacy for future generations?

I think you can find a deeper meaning there. I, as the author, cannot, nor do I wish to, verbalise it. I would like my statues to be perceived as a window to an irrational space, or as a guide through a space associated with emotions and spirituality. I would like them to function in time, reflect the present and be capable of enduring into the far future. Statues from the distant past, whose link to present is not only their placement in their historical context, but above all their beauty, can and do have a message for us. I would be delighted if my statues, too, were capable of bearing such a message.